Genesis 3:16 contains no mention of pain in childbirth

Intentionally provocative title, but I find the argument persuasive

I’m still drowning in Genesis commentaries, and here’s something I thought was interesting. I came across an argument that Gen. 3:16 contains no mention at all of pain in birth.

Let’s take a look at some English translations of Genesis 3:16. This is after the man and woman eat from the forbidden tree. God gives them what are often called “curses” but it’s worth noting that only the serpent and the ground are cursed; the man and the woman themselves are not cursed. So I’ll use scare quotes: this is the “woman’s curse”:

RSV:

To the woman he said,

“I will greatly multiply your pain in childbearing;

in pain you shall bring forth children…

NAB:

To the woman he said:

I will intensify your toil in childbearing;

in pain you shall bring forth children…

Sarna (one of the commentators) draws an intriguing connection between the forbidden tree of knowledge of good and evil and the fact that human babies have larger heads (proportionally) compared to otherwise comparable mammals. The implication here is that the knowledge gained by eating from this tree increased the size of the human head, and the baby’s large head is what makes birth painful — or, if this isn’t actually how it happened, it’s at least interesting to think about and worth considering if there is some real etiology here.

I pitched this idea to a group of moms, sort of wondering if there would be a broad consensus for or against this idea in light of their experiences of birth. I didn’t get one.1 The consensus I did get was from the women who had experience helping animals deliver their young, who told me it does not appear to be less painful, less uncomfortable, or less terrifying for sheep, goats, cows, dogs, cats, etc. compared to their experiences delivering their own (human) children.2

Why do human mothers need help (e.g. from midwives) to deliver their babies but animals in the wild don’t? The answer seems to be: the animals in the wild do need help, but nobody cares and so a lot of them just die. We don’t care much about animal mothers in the wild, so they go without assistance; farmers and breeders care about their animals, and that’s why they help with their births; we care intensely about human mothers, and that’s the reason for the heroic Hebrew midwives Shiphrah and Puah in ancient Egypt, and the entire modern medical field of obstetrics.

But what about labor pains?

One woman posted this video in response to my query, which I found really interesting. It’s about 15 minutes long and aimed at a popular (smart but not scholarly) audience. The speaker makes a case that, based on the Biblical Hebrew, Genesis 3:16 does not refer to birth pain at all.

He walks the audience through the argument and notes a pastoral concern that is not uncommon: the idea that Adam’s “curse” is for all humanity (we all find work difficult! This is a human experience, not a male-only experience) and women have this additional added-on “curse” of birth pain (which may be synecdoche for all of the suffering involved in having female-specific organs/systems/bodily functions, in which men obviously do not participate at all).

It is easy to draw harmful conclusions from this: women are extra cursed; women are therefore extra guilty; I ought to carry this shame with me in everything I do because Eve and I are both women; pain mitigation in birth is by its nature sinful; painful symptoms in female-specific bodily organs are our punishment for the sin of Eve and not something appropriate to ask a doctor about; sexism is obviously a completely appropriate way for men to relate to women, etc. Not every woman carries around these heavy (and false) beliefs, but I do know it’s not an uncommon burden for women, especially historically.

What would change if Gen. 3:16 made no mention of birth pain at all?

The speaker in the video referred to the scholar who put this argument together, and I went and looked him up. It seems that said scholar and others put together a collection of essays in honor of a beloved professor/mentor’s 65th birthday, which is endearing; the important thing is I was able to access this essay online from our library. I want to outline his argument here. Buckle up, it’s going to be nerdy.

Some notes, first:

The title is “Pain in childbirth? Further thoughts on ‘an attractive fragment’ (1 Chronicles 4:9-10)” by Iain Provan, in the book Let Us Go up to Zion: Essays in Honour of H.G.M. Williamson on the Occasion of His Sixty-Fifth Birthday. If you want to look it up and need more bib info, let me know.

My Hebrew is… extremely beginner, and mostly what I know is how to wield a concordance. I have discovered that copy/pasting is likely to be a disaster (ask the professor who used the term “valiant attempt” in reference to my use of Hebrew in my Psalms paper a year ago). If you’re proficient in Hebrew, I’m happy to accept corrections.

Okay, here we go.

Let’s start with the relevant section of Genesis 3:16-17. I bolded the words that we’ll talk about.

Here’s the NAB:

16 To the woman he said:

I will intensify your toil in childbearing;

in pain you shall bring forth children.

…

17 To the man he said:

…

In toil you shall eat its yield

all the days of your life.

And the RSVCE:

16 To the woman he said,

“I will greatly multiply your pain in childbearing;

in pain you shall bring forth children,

…17 And to Adam he said,

…

in toil you shall eat of it all the days of your life

Provan’s argument, as I understand it, follows. As far as I can tell, it checks out.

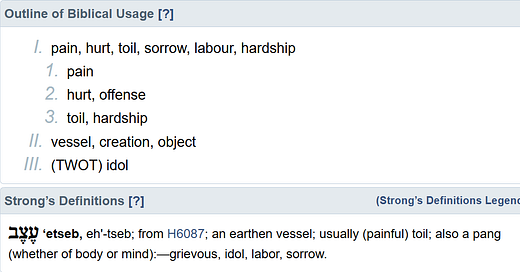

First point: the word translated “pain” here (“in pain you shall bring forth children”) is not the word for birth pain. The word is spelled bet-tsadee-ayin and pronounced something like “etseb,” and you can find the dictionary entry here. (Hebrew reads right to left. Bet is the Hebrew letter that sounds like the English B.)

Hebrew has a few other words that specifically refer to labor pain (Provan lists them; I’m not familiar with them, but I imagine they’re comparable to “contraction,” i.e. words that very specifically refer to the pain involved in birth). If you look at how this particular word, “etseb,” is used elsewhere in the Old Testament, it never refers to birth pain; rather, it normally means emotional pain, pain involved with work, and more generalized pain.

Second point: I suspect Provan would prefer the NAB to the RSV here, because the NAB uses the word “toil” for both the woman and the man, and that mirrors the Hebrew. The Hebrew is nun-vav-bet-tsadee-ayin, “issabon.” (I suspect it is grammatically related to “etseb,” because the bet-tsadee-ayin is the same, but that’s all I can say about that.) The important point is it’s the same word, and it makes sense to assume that the author is intentionally drawing a parallel. Dictionary entry is here.

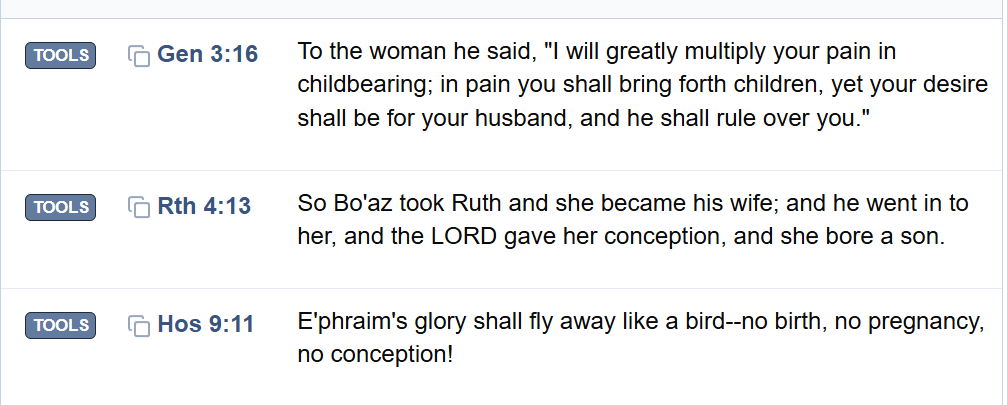

Third point: The word translated “childbearing” (“herayon”) is not the word for birth, or for pregnancy. It is the word for conception. The dictionary here says that it can refer to pregnancy or conception, but a few of the examples seem to indicate (with Provan) otherwise.

Here’s the dictionary entry:

But look at where else “herayon” is used in the Bible:

In the Ruth passage, we find both words, conceive and give birth. These are two separate words in English and two separate words in Hebrew, and the word we saw in Genesis “herayon” is the word for conceive, not give birth.

We see the same thing in Hosea. Here, we see the words for birth, pregnancy, and conception, and “herayon” is right there for conception, but not the other two.

All this to say, third point: the word translated “childbearing” actually means “conception.”

Point 3.5: I didn’t find this in Provan, but I looked up the second phrase, “bring forth children.” The Hebrew word is “yalad.” It seems to be that “bring forth children” is a good translation, because it’s more general than the specific process of birth. It’s frequently predicated of men and translated “became the father of…” and men, obviously, do not actually deliver the babies. Here are some other places where we see “yalad” in the Bible:

Fourth point: This phrase could literally be translated “pain and conception.” It could mean literally the multiplication of pain and the multiplication of conceptions. Provan suggests that the multiplication of conceptions implies miscarriage and infant mortality, tragic events that can cause a woman to return to fertility sooner than if her child had survived — which means, more conceptions as a result of pain and death.

But he also suggests a hendiadys, which is a two words connected by “and” that convey a single idea, e.g. “nice and hot” or “good and ready.” We don’t think of a person as being both good and ready, as separate things; it’s one idea. So, it could mean something like “I will multiply your painful/toilsome conceptions.”

Finally, Provan lands on this as a translation of this passage:

I will greatly multiply your sorrow and your conception; in sorrow and hardship you shall bring forth children.

Provan comments on this at length, suggesting that we see the word “pain” in a broader way,

as referring to the ‘agony, hardship, worry, nuisance, and anxiety’ of the circumstances into which children are born and then raised, and in which they die… Indeed, nothing forbids us from understanding it as referring, in part, to the same kind of challenging (painful) economic circumstances that are in view [in a separate passage that he considers] and which might be considered to contribute greatly to trouble within a home. (Provan, 290)

Provan is persuasive, in my opinion. The implication of his reading is that Genesis 3 does not contain a “curse” for all humanity (difficulty in work) and an additional female-specific “curse” (pain with birth), but that life is hard! everything is hard! the world is a really hard place to be in now! it’s hard to do the things that need to get done; it’s hard to raise kids in this environment; it’s hard to live with the awareness that these innocent, vulnerable, and oblivious little people whom we love so dearly are going to have to experience the difficulties of life! The pain and hardship is inescapable. We experience it here in the wealthy, industrialized, politically stable West, and if anyone could escape it, it would be us. Yet, here we are.

I have lots more thoughts on sexism, gender, the history of gendered work, whether men and women experience things in the same way, and so on, but — well, if you’re interested, you know how to find me. I need to stop because this is really long.

But, as always, I’m interested in your thoughts.

One woman provided a delightful image of Adam and Eve with balloon heads saying “it totally wasn’t me — it was her, it was the serpent” in the manner of a child with chocolate all over his face or wet pants claiming it was the other kid that ate the cake or had the potty accident.

I just started reading Stuart Little with one of my kids, and I’m horrified by the idea of giving birth and discovering it isn’t a human baby at all, but a mouse. I am all questions about Mrs. Little’s birth experience.

The idea that the curse will make both tilling the earth and the raising of children toilsome makes a whole lot more sense as a parallel of the preceding commission: 1) be fruitful and multiply 2) steward the earth. You’ve made your two jobs a whole lot harder for yourself but they are both the joint responsibility of the couple, not one and one.

Interestingly, older translations also seem to justify Provan. The Douay has "I will multiply thy sorrows, and thy conceptions: in sorrow shalt thou bring forth children..."

The King James: "I will greatly multiply thy sorrow and thy conception; in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children..."

The Septuagint seems to support this line of interpretation, particularly in that it uses the same word (lupe, grief (however, can also mean pain)) for both Adam and Eve.

On the other hand, the ESV (the most recent Protestant translation to gain widespread usage) agrees with the NAB and RSV/CE for Eve: "I will surely multiply your pain in childbearing; in pain you shall bring forth children..."; however, it also uses "pain" for Adam: "in pain you shall eat of it..."

The Tanakh (modern translation by the Jewish Publication Society, appears to be widely accepted) is similar, but also has the distinction between Eve and Adam: "I will make most severe your pangs in childbearing; in pain shall you bear children," and then "By toil shall you eat of it..."

With no knowledge of Hebrew myself but some experience with translation generally, my gut feeling is that there's a textual variant here, which is particularly suggested by the newer translations having the different reading. (Even without that, for the newer Roman Catholic translations there's also the possibility of having tried to follow the Vulgate more closely; the Vulgate differentiates Eve/Adam with dolor/labor. Although on that hypothesis the RSV/CE word choice seems a little odd because dolor is generally "sorrow" rather than "pain".)

I suspect - translation issues aside - that I wouldn't quite agree with Provan's final conclusion on the theology of the curse(s) but that's a guess from the brief quotations offered. Mackie's class (suggesting a parallelism between the curse on Eve and the one on Adam) is, I think, on the right track - and actually the interpretation I've heard taught. But then I grew up with the King James Version where the translation prompts the parallel - and the Reformed tradition, particularly the Westminster, has always insisted on "Adam's sin", at least formally, following NT examples, though in practice I'm sure blaming Eve has crept (back?) in.

Though, while that's a starting point, poking through the text right now has suggested to me that there's *more* than a simple parallelism simplifying to your "everything is hard" going on here, too. I'm just not quite sure what.